With great power comes great responsibility.

We all know the image of the strong man, holding up a gigantic weight atop impressively broad shoulders. But that image is a bit deceptive. In that strong man’s body, the legs are doing the majority of the heavy lifting. The arms and shoulders are what enable him to pick up that heavy object and carry it. All of that muscle mass you’re seeing in the shoulders makes a complex shoulder girdle that protects our shoulder joints.

Sitting at the top of our torso, our shoulders are incredibly mobile. Connecting our arms to our spine and neck, they are capable of broad, sweeping motions. This range of motion enables us to use our highly-dexterous hands and fingers to manipulate the world around us.

Shoulders are designed for mobility, hips for stability

Our shoulders have a wider range of motion than our hips simply because our arms need to be able to move in more directions than our legs. Our legs and feet are designed to carry us around, so our hips are pretty much concerned with moving us forward and backward. Our arms and hands are designed to interact with the world around us, so the shoulder can move in a full circle as we throw, push, and pull things in any which way.

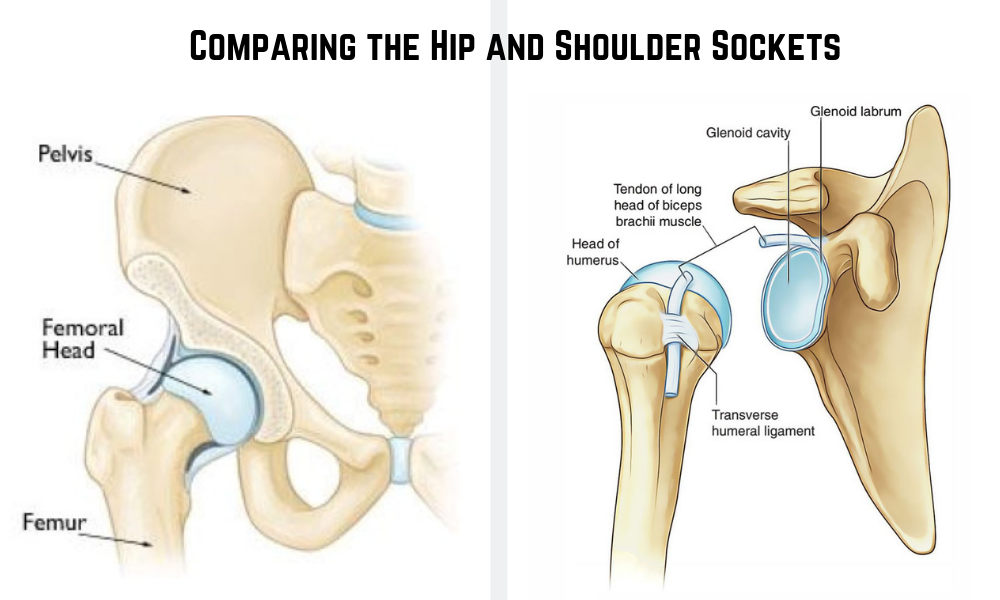

Both the shoulders and hips use ball-and-socket joints so they can rotate internally and externally, as well as flex and extend. But the shoulder socket is not as deep, bony, or inherently stable as the hip. If you compare the depth of the sockets, the head of the femur sits much deeper in the acetabulum (the hip socket) than the head of the humerus sits in the glenoid cavity (the shoulder socket).

This means that the shoulder has a greater range of motion, but it also means our muscles, tendons, and ligaments surrounding the shoulder joint have to do more work holding us stable. (That’s why it’s so much harder to balance on your hands than your feet!)

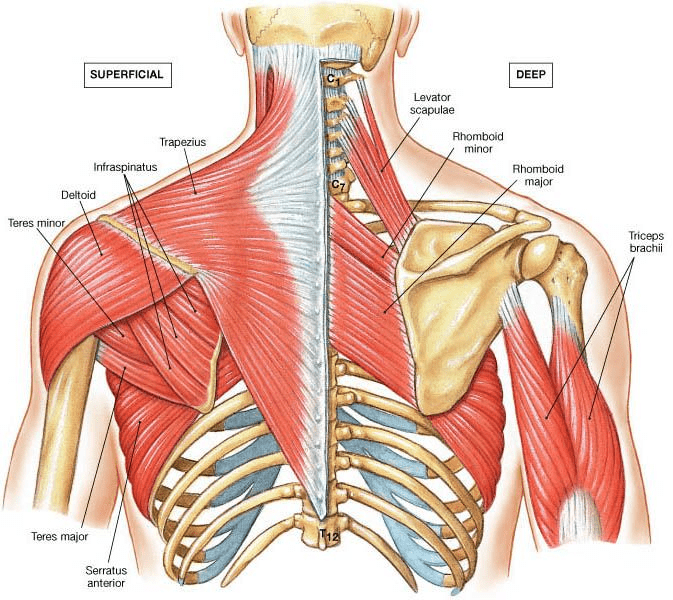

The shoulders have more muscles than the hips do, but they’re smaller. In this mass of the shoulder girdle, everything is connected. Muscles that move the shoulders, arms, and rotator cuff also impact the neck.

A link in the chain

You can think of all these little muscles and tendons running through the shoulders like a chain of dominoes… one impacts the next, with cascading effects on down the line.

In CF, this is why when we throw something out of whack when we cough intensely, we can sometimes feel it for days or even weeks afterward.

We have key nerves and arteries passing through this area too, so if you have any weakness in any of the “upstream” links in the shoulder or upper spine, this can cause a domino effect “downstream” that manifests as pain in the wrists and hands.

This complex structure in our shoulders has great power… but with that power comes great responsibility. By being aware of the unique construction of our shoulders and taking two simple steps, we can avoid a lot of potential injuries during our yoga practice.

#1: Stabilize the shoulders by retracting the shoulderblades back and down

The shoulderblade is a big, flat bone called the scapula. These bones don’t connect directly to the spine or ribs – they are held in place by six stabilizing muscles that attach onto the rib cage and the spine: the Trapezius, Rhomboids, Pectoralis Minor, Levator scapulae, Serratus anterior, and Latissimus dorsi.

In addition, the four muscles of the rotator cuff connect and stabilize the humerus in the shoulder socket: supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor, and subscapularis.

These muscles all work in tandem for stability, strength, and mobility.

(Image: PhysioLogic)

#2: Mobilize the shoulder by circle sweeping the arms

If you look at the picture of the shoulder socket in the top photo, you notice a tiny bony protrusion to the right of the shoulder socket. This is called the Coracoid Process, and it can interfere with the range of motion of the arm when you reach forward and upward.

So rather than limit our range of motion by reaching up directly overhead, we can sweep our arms out to the side in a circle to clear this bony protrusion.

This simple “circle sweep” of the arms makes poses that have an overhead reach a lot more accessible and comfortable!

The Coughing Accessory Muscles

Though the diaphragm and the abdominal muscles do the majority of the work that makes us cough, the coughing accessory muscles are recruited when those muscles fatigue, or need extra help.

The scalene and sternocleomasticoid — the big ropy muscles at the sides of the neck — contract when we cough deeply.

And coincidentally, during coughing we also recruit lot of those same shoulder-stabilizing muscles mentioned above (like the trapezius, serratus, and latissimus dorsi). For that reason it can be tiring for those of us with CF to create that shoulder stability . . . and it’s important to let those muscles relax and take a break during our yoga practice.

In my own practice, I favor side bends (to release the latissimus dorsi), neck stretches (to release the neck and trapezius muscles), and twists to balance everything back out.

We’ll incorporate some of these relaxing shoulder and neck stretches into the last class of our #AlignmentApril session, coming up on Saturday morning!