If you’ve ever joined a gym or watched a fitness video, or even casually browsed Instagram, you likely have encountered and internalized certain ideas about core strength.

We’re admonished to blast away the fat in pursuit of “killer abs.” Billboards and magazines are covered with images of abs chiseled to a superhuman degree. Over and over again, we absorb the message that rock hard abs are the best abs. Muscle=good, fat=bad.

This can be hard to reconcile against the reality of the human body, especially with the complexities of cystic fibrosis. For one thing there’s the visual body-image issues that accompany the “CF Belly.” Our bellies are often round as our digestive systems are working overtime trying to keep up. And we have to keep a healthy body weight, so we need to keep a layer of fat as a reserve in case we get sick.

There are also the deeper issues about our digestive health, ranging from intestinal obstructions to painful indigestion to urinary incontinence from frequent coughing. (If you’ve ever coughed so hard that you peed a little bit, you know what I’m talking about.)

So caring for our core is not only a visual thing, it’s a deeply personal issue for many of us.

“The body is like a boat on water, where the body is the boat and the external stimulus is the water. Both are stable and able to respond to the inevitable wobbles, turns, and shifts only when they are balanced.”

– Susi Hately, Anatomy and Asana

The fact of the matter is, caring for the core is much deeper than what’s visible on the surface, and core stability alone is just one part of the equation. In yoga, we work with both the anatomical body (the physical body), and the subtle body (the energetic body) to find balance.

In both the physical and the subtle body, there is more to core stability than meets the eye. We can practice caring for the core by remembering our ABCs:

A is for Abdominals

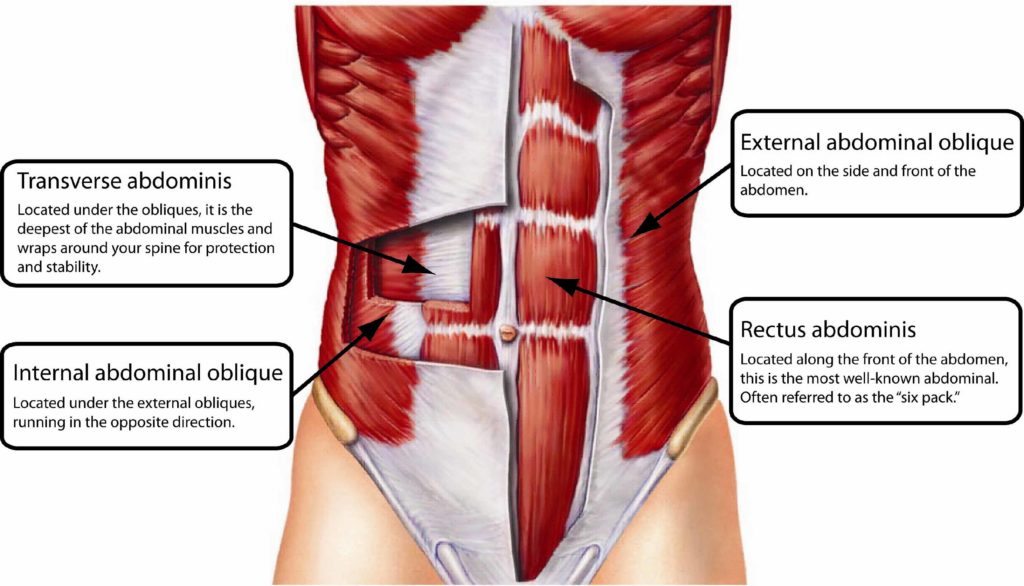

The abdominal muscles, which create core stability, are more than what we see on the surface. The abdominal muscles are layered, with four major muscles working together to create stability in different directions.

When most people think of “abs,” they picture the rectus abdominus, the surface layer muscle that runs vertically from the pelvis to the bottom of the ribs. It’s this muscle that has those segmented indentations which we can potentially see as “six pack abs.”

At the sides we have the internal and external oblique abdominals, which engage in our spinal twists and lateral flexion postures. The deepest layer is the transversus abdominis, with muscle fibers running horizontally around the body.

The transversus abdominis is the muscle that creates our deepest core stability, as it engages like a sling that holds everything together. Focusing on that deep engagement lets us build our yoga pose from the inside, out.

B is for Bandhas

The yoga Bandhas are “locks” or “seals” within the body that control the flow of “prana” – meaning life energy. They ground us physically and mentally. The three primary bandhas are all located along the trunk: one deep inside the pelvis, one at the solar plexus under the diaphragm, and another at the throat.

The Bandhas are about energy, not anatomy, but since they reside within the body they are of course affected by it. (Each of the bandhas correlates to one of the chakras, if you’re into that sort of thing.)

Jalandara Bandha, or “Throat Lock,” is the upper bandha, and typically the easiest for us to understand. It is accessed with a slight downward tilt of the head, the chin reaching down toward the collarbone while energetically creating enough space that we could hold an invisible apple in place.

Mula Bandha, or “Root Lock,” is the lowest Bandha in the body. It sits in the bowl of the pelvis, and it’s activated by lifting and engaging the muscles of the pelvic floor.

(Image: YogaAnatomy)

The pelvic floor is a network of muscles at the base of the pelvis, criss-crossing each other between the sitz bones in a diamond shape. You can learn to notice and control it with practice, just like you can any muscle, but the sensation is a little different for men and women.

For women, it’s most commonly experienced as the sensation that stops the flow of urine. For men, it’s associated with the lifting of the scrotum (like when you’re wading into cold water and have that moment when you want to tuck everything out of the way).

Knowing where this mula bandha lies in the body, you can see why it’s important for people with CF to practice it. These are the same muscles that can be strengthened to prevent or improve urinary incontinence.

In between is Uddiyana Bandha, “upward flying lock,” which is a belly compression lock under the solar plexus. It’s associated with deep cleansing of the digestive organs, and when you see a picture of this deep hollowing out of the belly below the ribcage, you can understand why.

While this may potentially have some appeal to those dealing with the digestive issues of CF, there’s also a trick to it that might make it a no-go: it requires fully exhaling (completely emptying the lungs of breath), using a “false inhale” to create a vacuum, and holding the breath for a few seconds.

(gif source: youtube)

If you’re anything like me, you can’t comfortably exhale all. the way. out. The sticky mucus lining the lungs is like glue, and when I breathe ALL the way out it results in a hacking, productive cough that leaves me gasping for breath. I intentionally breathe all the way out for my airway clearance a few times a day anyway (I do autogenic drainage), so I don’t feel a need to do that again during my yoga practice when it would leave me hacking in a ball on the floor (and completely take me out of the moment)!

If I’m ever in a yoga class where the instructor cues us to “breathe all the way out” or “activate Uddiyana Bandha,” personally I practice it slowly and minimally with a more subtle engagement of the deep transverse muscle, or even skip it entirely. Your mileage may vary. If you do want to try it, make sure you learn how from a qualified yoga instructor who will listen to your needs and concerns.

C is for Conscious Breathing

The relationship between the stability of the abdominals and the energy of the bandhas is rooted in the breath. The breath is the space where balance happens between the two.

Just like the diaphragm sits underneath the ribcage and provides a protective barrier between our lungs and our visceral organs, the pelvic floor functions as a second, smaller diaphragm that keeps those organs safe and protected from the outside world.

The relationship between the diaphragm and the pelvic floor is so strong, in fact, that one of the simplest ways to practice Mula Bandha is by coupling its physical motion with deep diaphragmatic breathing.

Exhaling we engage the pelvic floor, upward, inhaling we let it relax downward. This engagement of Mula Bandha as we inhale and exhale can naturally extend up into the abdominal muscles. Exhaling the abdominal muscles engage, inhaling they release.

This inherent connection with the breath means when we engage Mula Bandha, we physically and mentally support our core at its deepest levels. With awareness and practice, we can keep Mula Bandha active through both the inhale and exhale . . . even carrying it through our whole practice.

In yoga, core engagement is deep and subtle, coming from a fluid idea of doing “just enough and no more.” Caring for our core means learning to embrace the dynamic ebb and flow of our internal body and breath.

Our deepest core strength is not built through punishment, but through compassion.